As economic competition between China and the US intensifies, technology has become the primary focus. Separating the development, use and distribution of technology by the world’s two largest economies will create new risks and potential opportunities for investors.

Putting national security interests ahead of economic cooperation: The evolution of G2 deglobalization and its implications

A recent shift in US-China relations has far-reaching implications for businesses and investors.

Western countries are adopting a unified strategy to address China’s growing global aspirations and economic might. Their approach puts national security goals ahead of economic efficiency, a major departure from what most of the western hemisphere seemed to believe, as their economies evolved after World World II.

In a speech at the Brookings Institution this past April, President Biden’s National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, stated that the US is focused on “de-risking and diversifying, not decoupling” from China. As part of this approach, Sullivan said the US is following a “small yard, high fence” approach to guard advanced US technology against leaks to China and working to build a secure supply chain with friendly nations. EU leaders expressed a similar approach in their dealings with China.

Sullivan’s speech was significant because it signaled that the US sees limits on the transfer of technology and innovation to China as a means to increase its security. Technology is not a “small yard” when it comes to value-added products. This means more goods will need to be developed, designed and distributed away from China. And in response, China will need to invest in its own technology infrastructure to a much larger degree than it contemplated just five years ago. Such actions are “inefficient” in that costs for both China and the West will rise, and the benefits of globalization will fade.

Growing tensions

Even before Sullivan’s statements, investors believed the US had sought trade, technology, and economic decoupling with China. During the Trump Administration, most Chinese exports to the US were subject to 25% trade tariffs and many Chinese technology companies were put on lists that barred firms from accessing US technology and doing business in the US without explicit permission.

Since taking office, President Biden has left the tariffs unchanged and further expanded the scope of the Trump-era policies to further limit US companies from selling a wider range of technologies to even more Chinese companies without a special license. This comes after severely restricting the use of Chinese components in good produced by Western companies.

Compared to the Trump Administration, which effectively started a trade war with China, the Biden Administration has taken a more comprehensive, targeted and systematic approach to protect “vital US interests.” In short, the focus on ring-fencing access to advanced technologies represents a new type of deglobalization against a “strategic rival.”

Declining investment in China

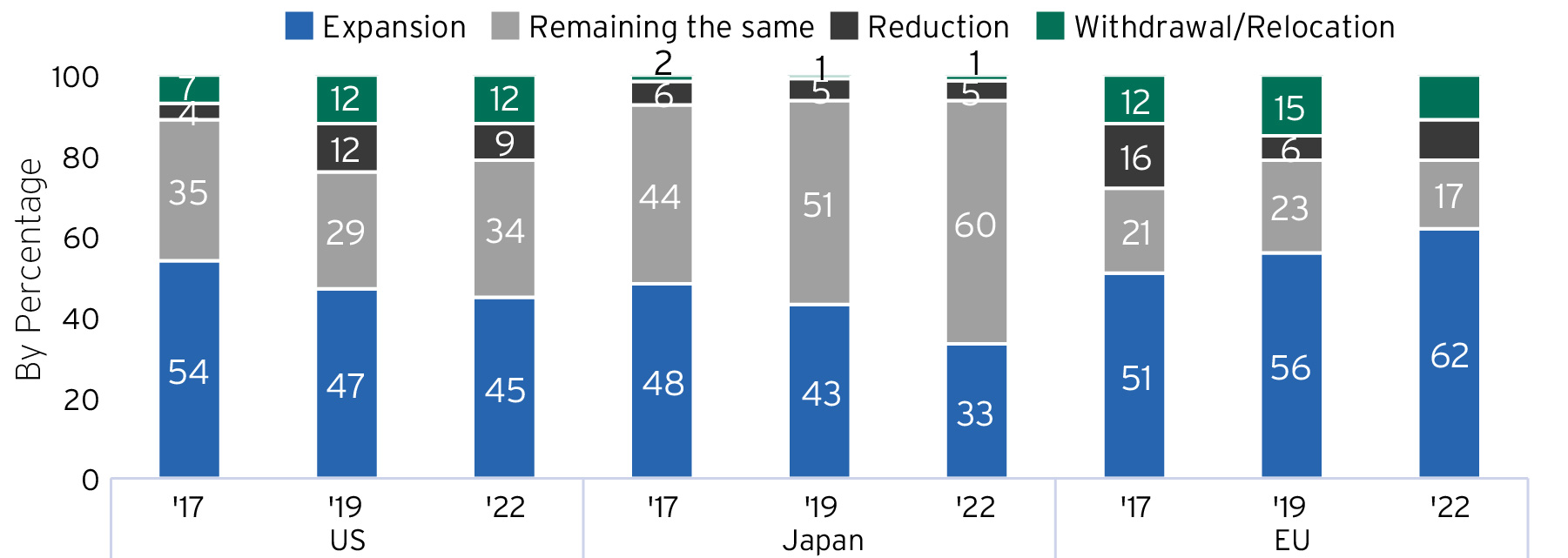

The sharp acceleration of this US policy is already impacting the willingness of multinational companies to expand or initiate new investments in China. Surveys from the American Chamber of Commerce in China and the JETRO, a Japanese government agency to promote international trade and investment1, show that only 45% of US firms intend to expand operations in China, down from 54% in 2017. Just 33% of Japanese firms said they intend to expand in China, down from 48% in 2017 (Figure 1).

Interestingly, European Union (EU) multinationals are heading in the other direction, with 62% intending to expand operations in China, up from 51% in 2017. More US firms have also reported an intention to move out of China, with 21% saying they intend to move in 2022, up from 11% in 2017. Japanese firms didn’t show the same inclination to leave, while EU firms are signaling an intention to stay, with just 21% saying they intend to leave, down from 28% in 2017.

Decelerating exports to China

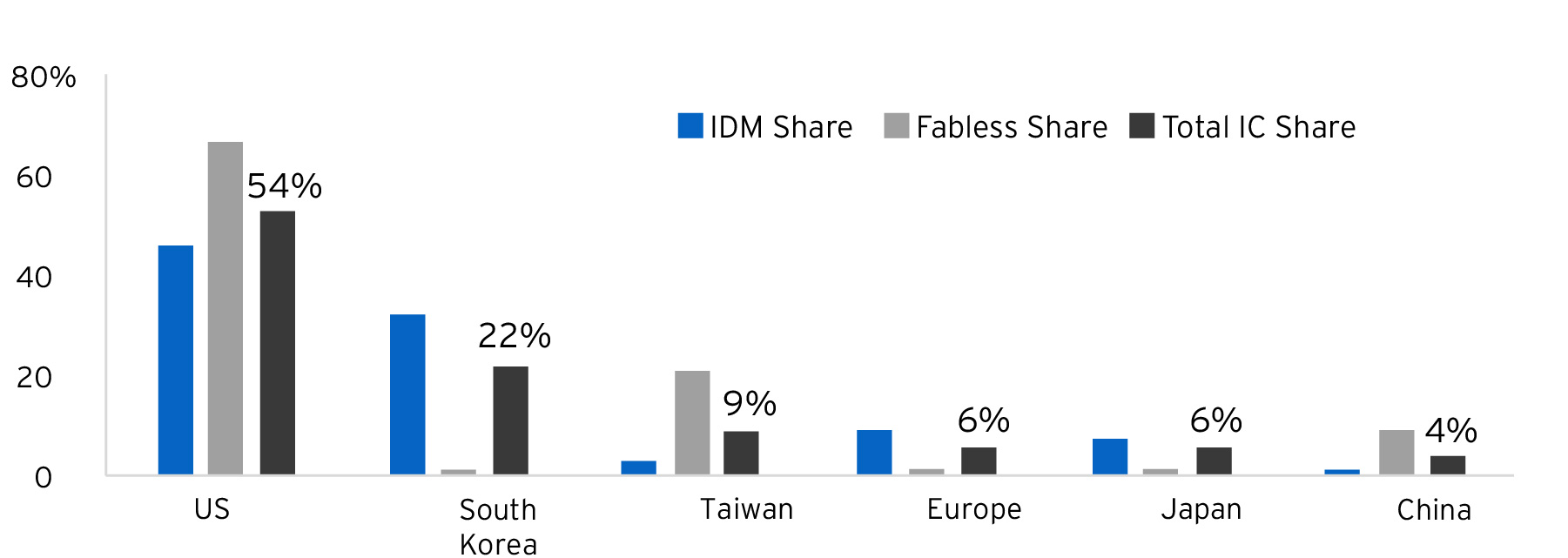

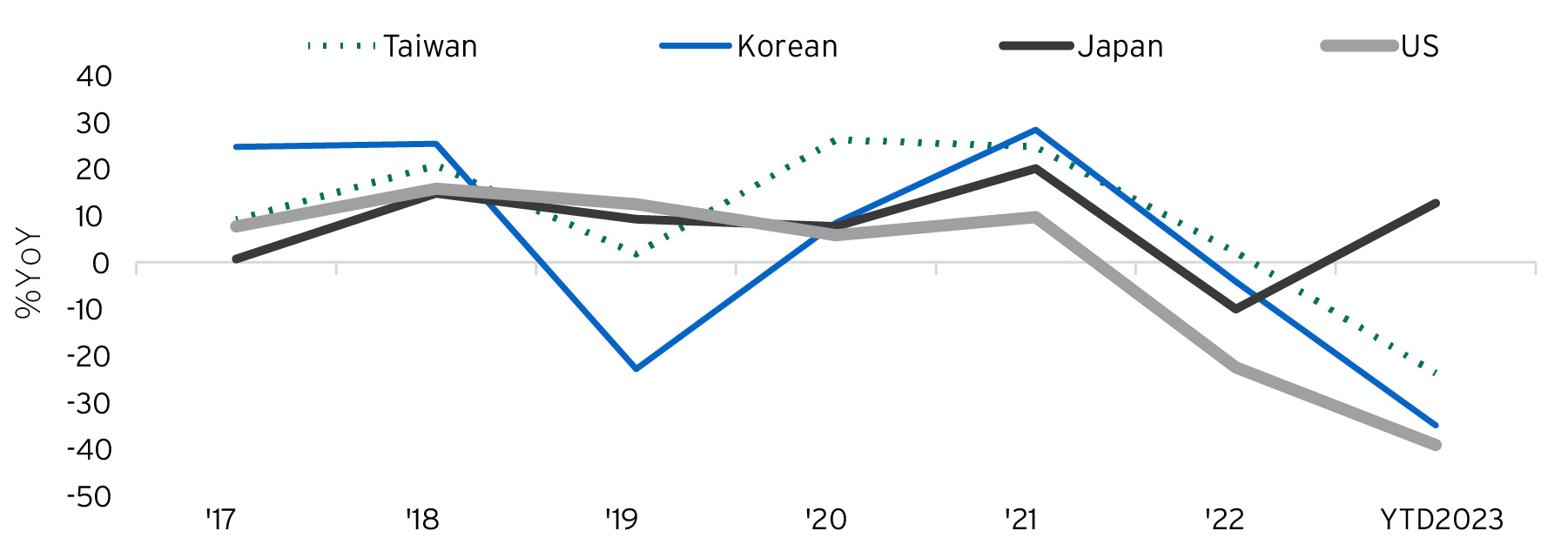

The “small yard, high fence” policy has already greatly impacted semiconductor makers. For US global semiconductor makers, which collectively represent 54% of global semiconductor production, the new regulations mean less business with China in the near term (Figure 2). US companies are withdrawing US personnel from their operations in China and are expected to move specific equipment and assembly operations to the US, Europe and elsewhere. The short-term impact is already showing up in the drop in exports to China. Among the key global semiconductor producers, Chinese imports from the US dropped by a staggering 40% year-over-year (YoY) in 2023 — the sharpest decline of any prior period (Figure 3). Despite the drop, we believe the potential for long-term growth prospects in semiconductors will more than make up for the loss of sales to China (see Generative AI: The beginning of (another) technological revolution).

What should investors consider?

The evolving relationship between the West and China will cause costs to rise.

Shifting G2 tech policies will have significant repercussions for corporate research & development (R&D) spend in China and the US, opening up potential new opportunities for investors. China has seen restricted technology firms rise in market value, just as Western suppliers have seen their share prices rally. While CIG are presently overweight China due to its rapidly improving macroeconomics, the slowing global economy and realignment of the West’s priorities will require even more selectivity in the building of Chinese investment portfolios, now and in the future.

The Biden Administration’s new industrial policies directly impact strategically critical sectors like supply-chain technology, smart manufacturing, semiconductor, biotech, green energy, space communications, aerospace technologies and new materials. US companies moving operations away from China will create new reshoring or “friend shoring” opportunities. Technologies such as robotics and AI and industries that secure critical natural resources allow for greater onshoring and nearshoring. Recent legislation – the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act and the CHIPS & Science Act – are all supportive of the development and investment of these technologies. CHIPS & Science, for example, directs $280 billion in spending over the next 10 years across R&D, manufacturing, workforce development and tax credits.

As companies look to replicate advanced technologies in North America, the need for robotics and AI technology expands, given that higher labor costs are inevitable with onshoring.

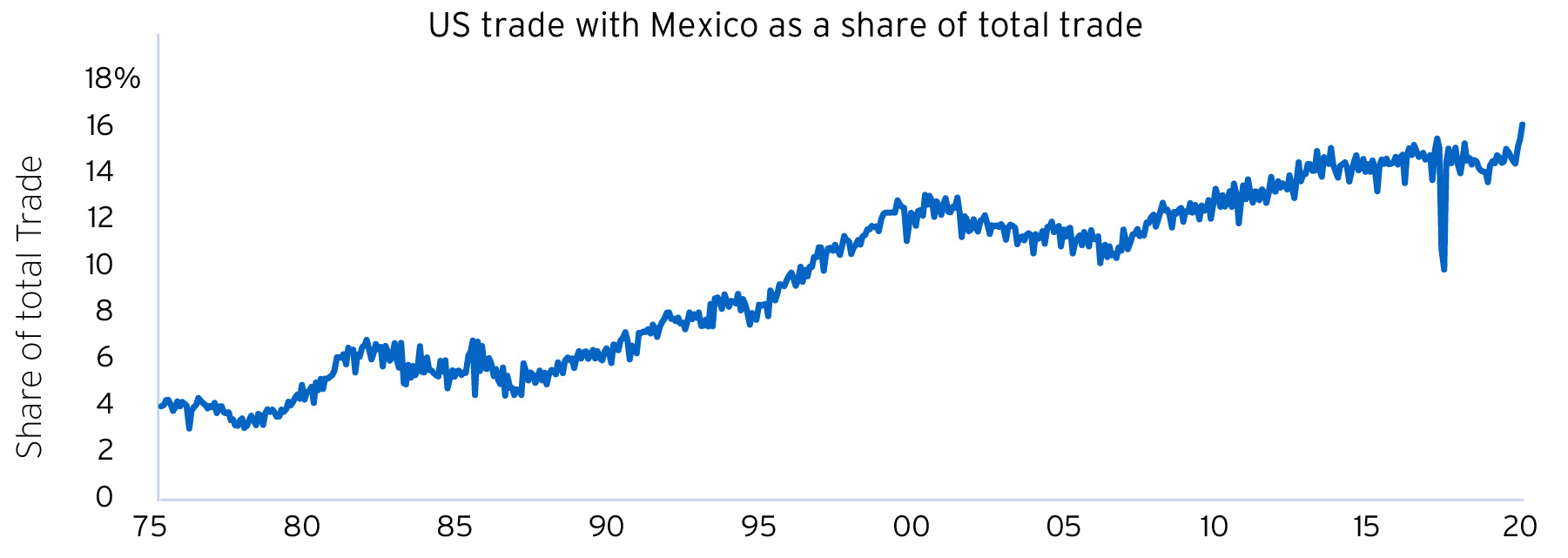

US neighbors like Mexico also stand to possibly benefit from nearshoring. The 2020 passage of United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) as well as US policy preferences such as the North American final assembly, all tilt the playing field in favor of Mexico and Canada. Indeed, Mexico is capturing an increasing share of total US trade (Figure 4). Logistics and transportation companies can be attractive investments, as are sectors that benefit from the rise of the Mexican consumer. Financial institutions may also do well as more people in Mexico enter the formal economy.

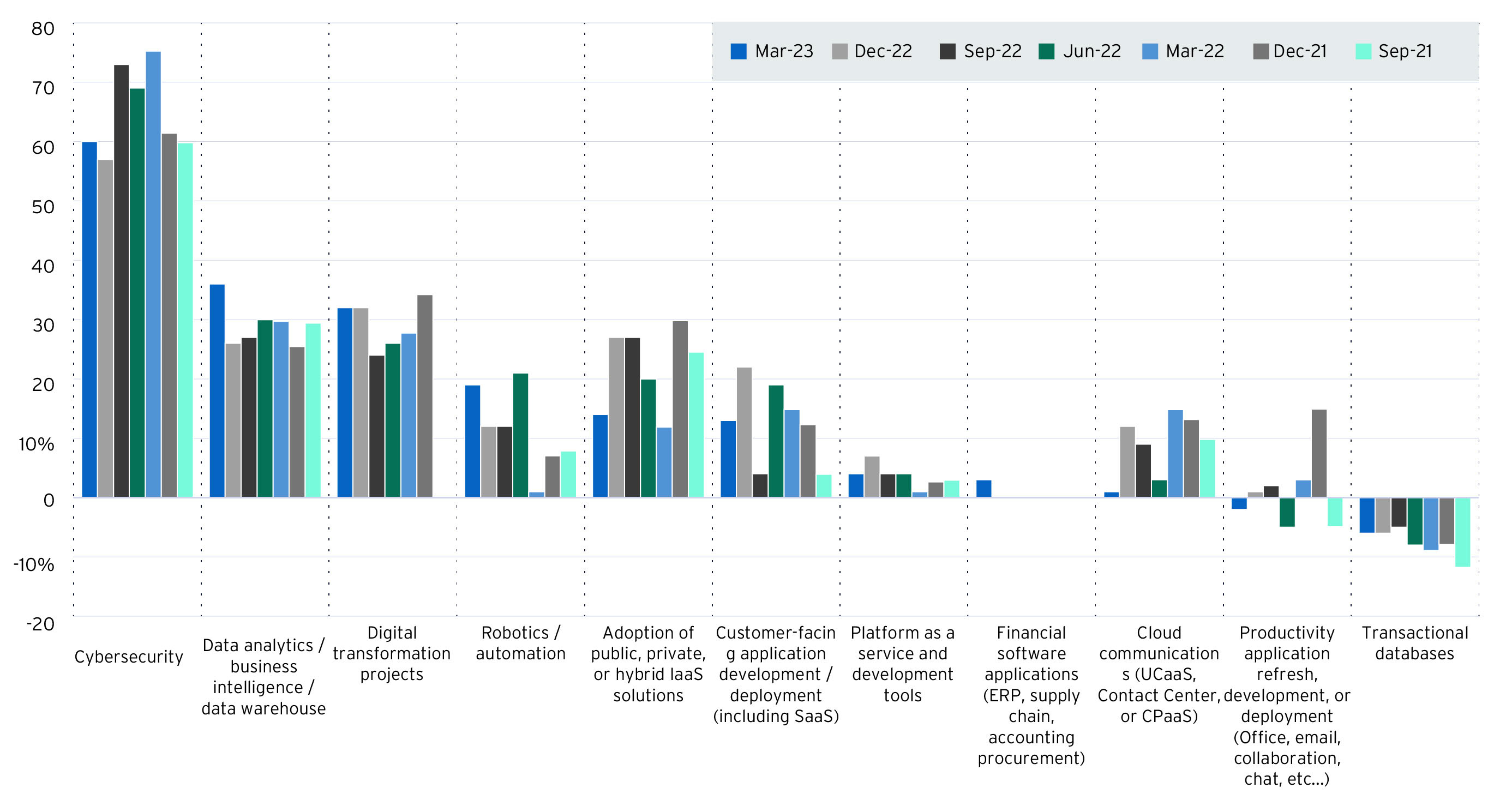

Cybersecurity is another high-quality subsector that may benefit from larger defense budgets. We look for companies that are focused on the privileged access management space and those specializing in the proactive identification of cyber threats and marketing corporations. Demand for these services is expected to stay strong as chief information officers make cyber defense a bigger priority (Figure 5).

Both defense and cybersecurity both stand to potentially benefit from the long-term repercussions of a G2 polarization as the US and its allies dedicate more resources to national security. Before the Ukrainian/Russian conflict, investments in defense were focused on drones and advanced communications, but now countries are spending more on aerospace and defense. We look for companies that are part of the defense supply chain, such as makers of instrumentation and digital imaging, as well as companies with existing demand from the US and its allies, such as Germany and members of NATO.

Even if the balance of power oscillates in the White House or chambers of Congress, the stance of more protectionist trade will be steady. We are intent on seeking to identify the industries that may benefit from the inevitable “high fence” the US will put up to keep others out in this increasingly polarized G2 world.

To help put you in touch with the right Private Bank team, please answer the following questions.